Shlyuz Implant Framework: Part 1 - Influences

by Und3rf10w

Overview

I’m excited to finally discuss and share the Proof-of-Concept code for an implant framework I wrote called Shlyuz (шлюз). Shlyuz takes a number of design queues from the Assassin Implant developed by the Central Intelligence Agency as described in the Vault7 Leak from WikiLeaks. Some additional inspirations were taken from some other projects and presentations such as the excellent Flying a False Flag presentation from Blackhat 2019 by Nick Landers, among others.

Disclaimer: For reasons that should be obvious, I will not be directly linking to WikiLeaks in this post, but I may embed images or make references to various leaked classified documents. Do with that warning what you will.

Prior to releasing the source code of the Shlyuz framework, I’ll be releasing a series of posts that cover some background, design decisions, and lessons learned. This first, particular post will not dive into much into Shlyuz itself yet, but that will be done in future posts of this series.

Why write this?

I’ve written before about my belief that implementing a C2 is a a great way to get familiar with a programming language. At the time I wrote Shlyuz, I considered myself to be not even a decent programmer. Writing Shlyuz provided me the opportunity to explore a number of concepts that I wanted to get more familiar with such as:

- rotating communication channels

- split server/client/console infrastructure design and implementation

- symmetric and asymmetric cryptography for communication and transactions

- Modularization and plugin design

- Secure storage of configurations

- authentication

- multi-platform implant support

- microservice design

- Message queues

- asynchronous design

- protocol design

These are quite lofty goals, especially for someone that’s a self-taught programmer, but this seemed like the perfect project to attempt to learn and combine some about these concepts through implementation and design.

I’m a huge fan of system design that is as deniable as possible, and Vault 7 provided a rare window of opportunity to understand how groups that rely on this concept implement it.

Assassin - The Shlyuz Design Inspiration

Before I dig into Shlyuz itself, I think it will be helpful to get a solid understanding of the design inspiration that led to the creation of Shlyuz, which again, as previously mentioned was Assassin.

The Assassin user guide Concept of Operations describes it as:

…an automated Implant that provides a simple collection platform on remote computers running the Microsoft Windows operating system. Once the tool is installed on the target, the implant is run within a Windows service process. Assassin will then periodically beacon to its configured listening post(s) to request tasking and deliver results. Communication occurs over one or more transport protocols as configured before or during deployment

I interpreted that as being straightforward; a Windows implant talks to LPs (listening posts), gets tasks and delivers results. Basically sounds like literally every other implant. One thing that stuck out to me though was the last sentence in the concept of operations: “Communication occurs over one or more transport protocols as configured before or during deployment”. (Emphasis mine).

Having an implant capable of communicating over multiple transport protocols that can be swapped sounded intriguing to me, so I dove further into its capabilities.

Galleon Standard

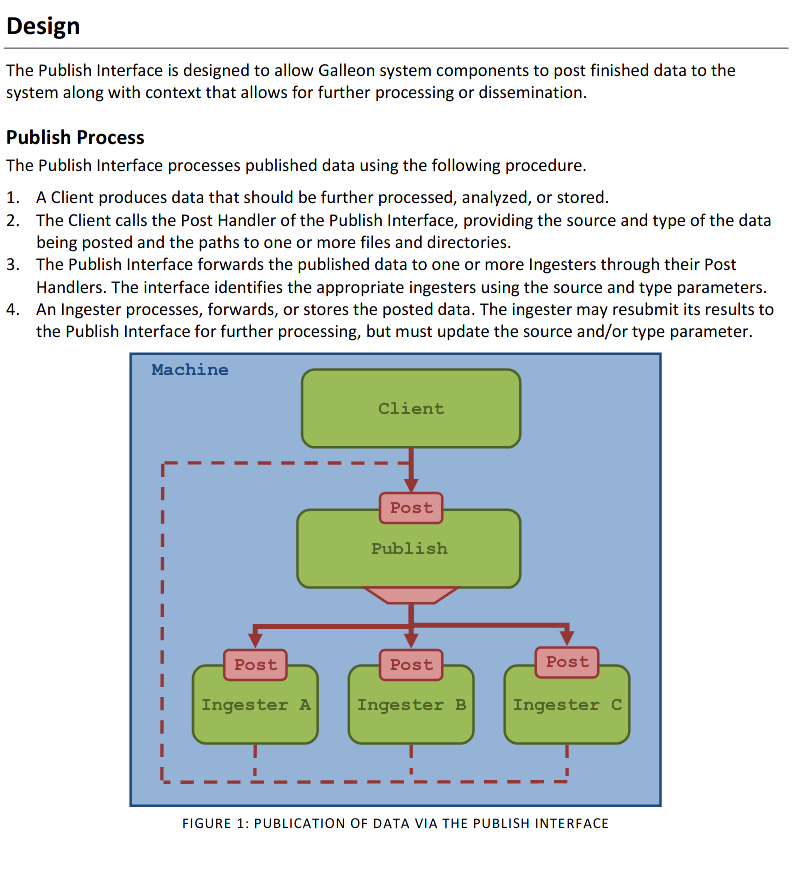

Assassin subsystems are apparently compliant with a set of standards called Galleon, which provides a specification for allowing a system to have a layed architecture and has interfaces for logging, transport, and publishing.

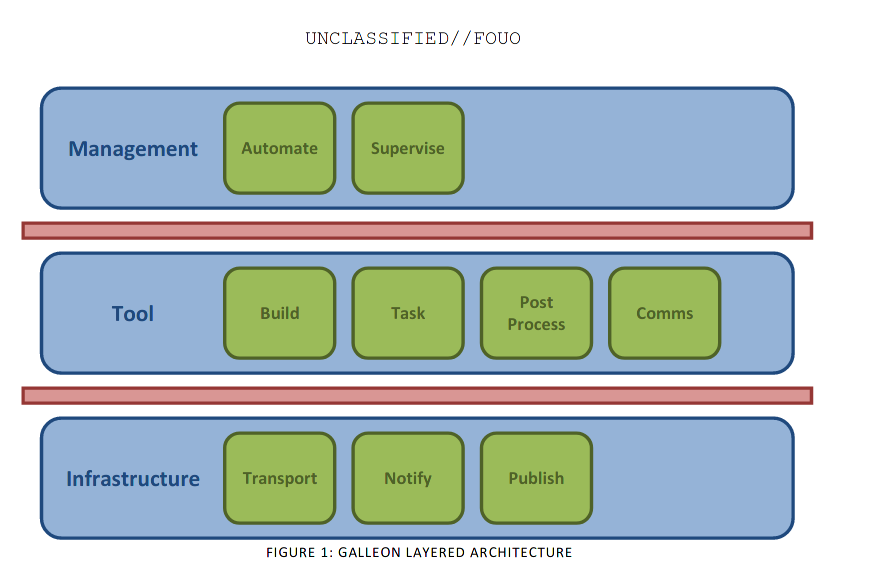

The Galleon architecture can be represented as:

I like this model, as it promotes dividing the system into components in each layer.

In addition, the Galleon model has three standard interfaces (as taken from Galleon-Design.pdf):

| Interface | Description |

|---|---|

| Transport | Provides services for the transmission of data between components in a Galleon system. This allows components to interact between machines without knowing any details of network or machine configuration. |

| Publish | Provides a mechanism for processing and exporting data from a Galleon system. System components will be able to post data to the system without any awareness of how that data will be handled by the system |

| Log | Provides a mechanism for recording events that occur in a Galleon system |

Galleon interfaces expose their functionality through handlers, which are called by executables, which implements the appropriate interface.

Frankly, I wasn’t interested in “recreating Assassin”, but this was a neat model to use for inspiration.

Galleon Transport Interface

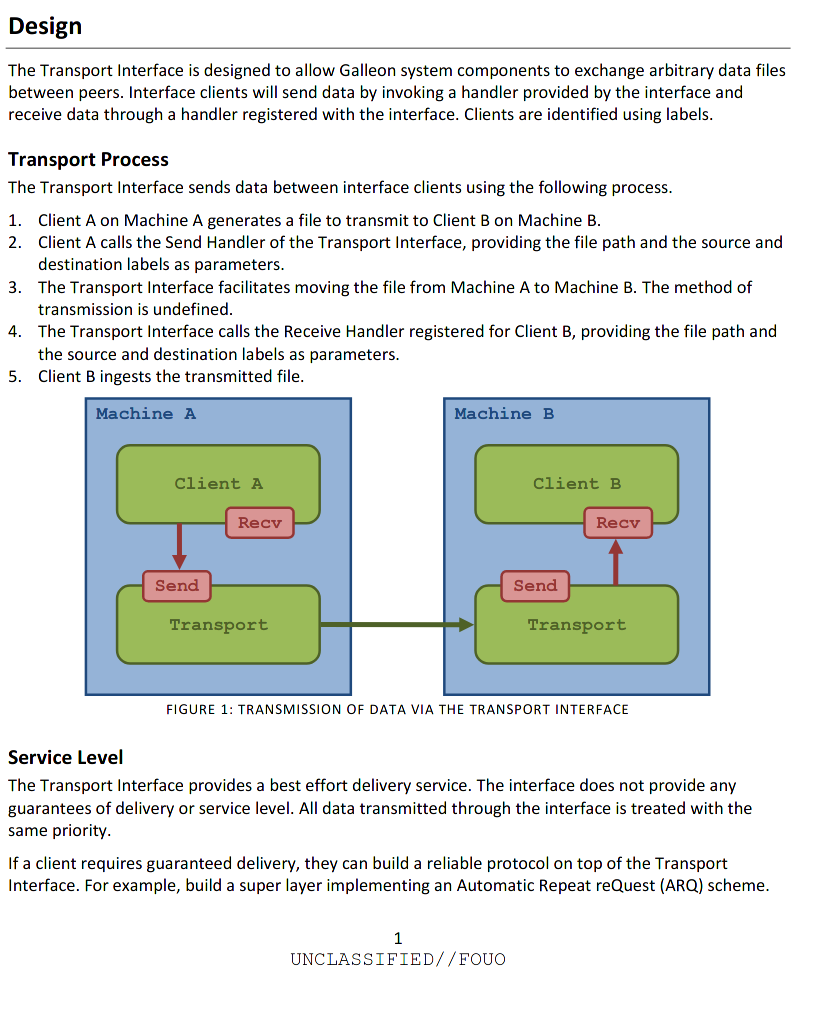

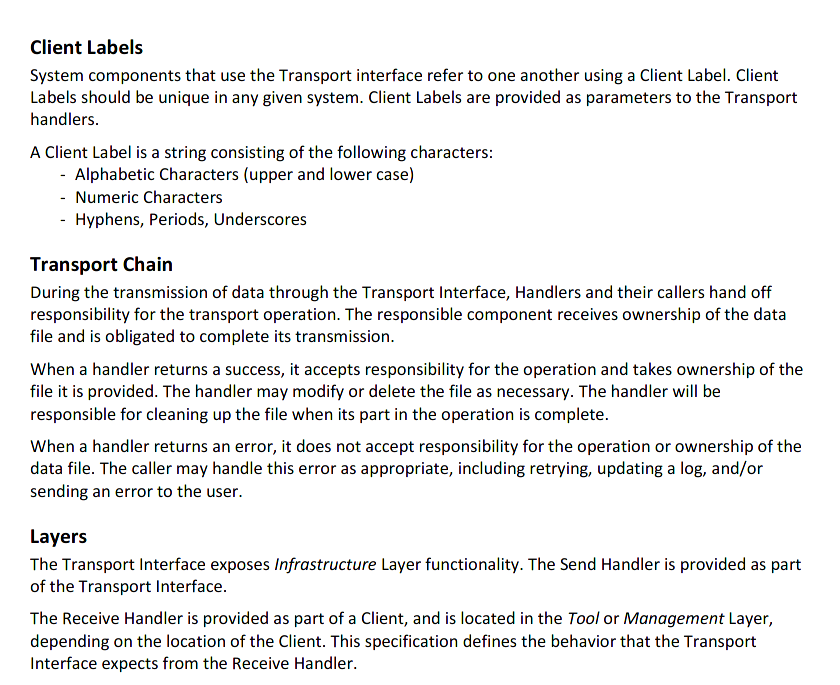

With one of my interests being weird ways to do transport channels, it’s a useful exercise to gain an understanding of what a Galleon Transport Interface might look like. Transport interfaces are “…used to transmit arbitrary data between components that may or may not be on the same machine”.

Rather than trying to explain the transport process myself, showing an excerpt of the design document would be more advantageous:

This logic can also be represented as the following sequence diagram:

An important takeaway that’s mentioned here is:

The interface does not provide any guarantees of delivery or service level. All data transmitted through the interface is treated with the same priority. If a client requires guaranteed delivery, they can build a reliable protocol on top of the Transport Interface. For example, build a super layer implementing an Automatic Repeat reQuest (ARQ) scheme

There wasn’t much in the way of what their ideal ARQ scheme might look like, but one can likely assume it relies on retying the transaction. Keep in mind this document is fairly old, one concept I would like to dig further into is verification that the data received is the data that was actually expected.

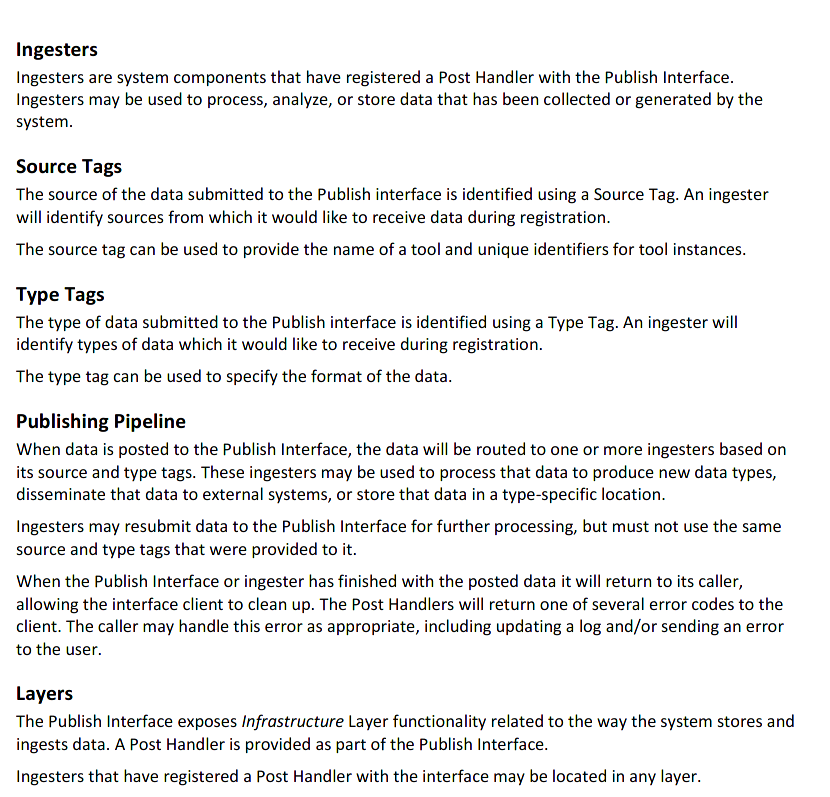

Galleon Publish Interface

The publish interface is used to post data that’s ready for further processing or operator consumption. It “…provides an abstraction… used to process, store, and disseminate data collected or generated by the system”.

Essentially, the client generates some sort of data, calls the post and publish handlers, the publish interface routes it to the appropriate ingestor(s), and the ingestor does the whatever action it requires, all while maintaining the source and type of data being posted.

This is a fairly logical and easy to understand pipeline that allows for accurate auditing of data as it moves through the system.

Galleon Log Interface

The log interface… describes how to do logging… There’s really nothing revolutionary here, so it’s really not even worth reviewing for the purposes of this post.

Assassin Subsystems

Now that we have an understanding of the standards that Assassin had to conform to, we can look at the components (referred to as subsystems) of the framework:

- Implant

- Runs on the target hosts. Configured using the builder and deployed to the target

- Consists of an implant and/or deployment executable

- Builder

- Makes implant and deployment executables. Operator configures them

- C2

- Interfaces between the operator and listening post.

- Generates tasks for the implant, sends them to the listening post, processes results, and handles logs

- Consists of the user interface, task gnerator, queue proxy, ingestor, and log extractor

- Listening Post (LP)

- Facilitates communication between an implant and the c2 subsystem

- Consists of the beacon server, queue, and log collector

Shlyuz Subsystems

I liked the model somewhat implemented by Assassin, but I wanted to go further and landed on a model for Shlyuz components that went further in segmenting components; taking additional design cues from shadow and Cobalt Strike. I’ll quickly touch on the various Shlyuz components, but will dig further into the Shlyuz architecture in a future post.

- Implant

- It’s an implant, what do you expect?

- Builder

- Builds the implants, self-explanatory

- Listening Post

- Designed to be extremely lightweight and deniable. Facilitates communications between implants (embedded), or between implants and the teamserver

- Teamserver

- Receives and issues commands to listening posts from operator console(s)

- Operator console

- Issues commands to the teamserver and displays outputs to the operator

Again, quite similar to the Assassin design, but a bit more segmented.

Assassin Multi-platform support

Section 1.4.2 lets it be known that Assassin scripts are written for Python 3.3, and that these scripts may run on any platform and operating system that runs a Python interpreter. This was great news to me at the time as I knew I wasn’t crazy for thinking I could implement this in Python.

The Assassin Implant

The Assassin Implant itself is what provides functionality of the toolset on the target machine it is running, “including communications and task execution”. There are a number different deployment methods available, as described in sections 2.1 to 7.1.3 in the Assassin user guide. Having all of these options is great, but since I don’t have the resources of taxpayers at my disposal, I didn’t really care about making a number of different deployment options available for Shlyuz. I do recommend you review their deployment options however, as it’s a pretty good read.

Implant Identification

As described in section 7.2, each Assassin implant contains a case-sensitive, eight-digit string that uniquely identifies each implant. The ID contains two parts, the parent and child. The parent identifies the group of implants set by the operator at build time, and the child is randomly generated on first execution unless otherwise defined.

By having an implant have a parent ID, they are restricted to only allowing one implant to execute on a host per parent ID.

My personal hypothesis is that the parent ID is likely used to identify either the target environment or “campaign” that the implant is being used on. The only drawback I see to this approach is handling cases where you have to execute another implant in order to obtain higher privileges, but I’m sure they accounted for that.

Implant Beaconing

Like most implants, Assassin communications are organized around periodic beacons. During a beacon event, it connects to the LP ands sets information about the state, checks for tasks, and responds with results. This is primarily covered in detail in section 7.3 of the user guide, but the beaconing model is very similar to most modern beacon implementations.

A few interesting points to note though:

Section 7.3.1.2 describes the manifest of data sent to the LP during a beacon event:

- Implant ID

- Machine time

- Time when implant last started

- Time when implant is scheduled to uninstall

- Index of Transport used to conduct current beacon

The last point is interesting as it signifies the capability for an implant to use different transport mechanisms.

Beacon Timing

Section 7.3.2 describes beacon timing with the following algorithm:

if (comms_succeeded):

interval = default_interval

else:

interval *= backoff_factor

interval += RandomInteger(-jitter, jitter)

if (interval > max_interval):

interval = max_interval

An interesting feature of Assassin I haven’t really seen much in other frameworks is the backoff_factor, which modifies the interval after a failed attempt to beacon.

Also mentioned, but not present in the given algorithm, is the initial_wait variable, which describes how long the implant must wait after startup prior to attempt it’s initial beacon.

Implant Tasking

If there’s one lesson I learned writing Shlyuz, it’s that asynchronous tasking is fucking hard! Thankfully, section 7.4 goes into extensive detail on how tasking works within Assassin, which gave me some insight on how to implement it for Shlyuz.

A task consists of one or more commands, which are the executed in sequence until they are all executed, or until an error is detected. A task can be used to encapsulate several interdependent commands.

A task can be set to run on receipt or run on startup.

run on receipt- Run the task as soon as it’s processed by the implant

run on startup- Task is copied to the implant’s setup directory and executed every time the implant starts

I really like the idea of run on startup, but an improvement I would make to the tasking is providing the ability for a task to soft fail instead of always doing a hard fail. For example, if the operator issues a series of tasks, and for some reason one of those instructions encounters an error, all following instructions will not execute. This is not always ideal from an operator perspective.

Finally, a task can be configured to push results immediately to the LP.

Section 7.4.3 describes that an operator can also add tasks outside of the framework by placing it in the relevant startup or input directory, depending on whether they want the task to run on receipt or run on startup.

Tasks are described as blocking; another feature improvement I’d suggest would be to set tasks to be the introduction of a flag that allows a task to be able to execute asynchronously, not blocking the execution of subsequent task(s).

Implant Communication

Section 7.5.1 describes how an implant can be configured to communicate using one or more transports. An implant is configured with an ordered list of transports, and the implant will attempt to iterate through them in the event of a failure. It is not clear whether this list of transports can be modified after execution.

Implant transports are done soley over HTTPS using the WinInet API with Firefox user agents.

As described in section 7.5.4, Assassin has a chunking feature, allowing the operator to set a limit on the amount of data that’s uploaded from the implant to the LP during a transaction. There is a hard limit of 1GB chunks.

Finally, of note is section 7.6.3, which describes a failure threshold feature. If the implant fails to communicate more than the configured number of times, the implant will automatically uninstall itself from the target.

Implant Configuration

Section 7.7 describes how implant configurations work.

7.7.1 says that an implant has 3 configuration states, running, persistent, and factory:

| State | Description |

|---|---|

| Running | Settings the implant is using to operate. Stored in memory and lost when the implant restarts. |

| Persistent | Settings the implant will revert to upon startup. Stored as a patch in the binary, otherwise saved as a file in the startup directory |

| Factory | Settings the implant had when it was built and originally deployed. Can be reverted to this state at any time by the operator |

Implant Crypto

Section 7.8 describes the cryptographic mechanism used by the implant. Basically it uses a modified RC4 stream cipher, and any data sent is encrypted prior to potential exposure. The implant carries a sixteen byte key that is patched into the binary. A sixteen byte session key is generated by combining a four byte nonce with the key and calculating the MD5 hash. A new key is calculated per crypto transaction, while the nonce is prepended to the crypt text before being stored or transmitted.

I found the constant rotation of the session key interesting and took some design inspiration from this model when writing Shlyuz.

The rest of the user guide basically covers the usage of the various components, installation, configuration, usage, and frequently asked questions. These sections are great if you’re trying to build an exact replica of Assassin, but that was not my intention with Shlyuz.

Shlyuz Design Goals

Armed with a general understanding of Assassin design and architecture, I started to get a vision of what I wanted the Shlyuz framework to look like and how to architect it.

The Shlyuz framework set out to accomplish a number of design objectives:

- Modularization of various components

- Inclusion of an artifact factory (builder)

- Multi-platform implants

- Multi-platform listening posts

- Separation of each component so that they can be ran as a microservice

My thought was that modularization could be achieved through the implementation of common protocols between components. Ideally this protocol would allow for communication between individual components regardless of their implementation so long as they adhere to the protocol.

This common protocol should be designed to be auditable, scalable, authenticatable and generic enough to be reusable.

This common component protocol model provides a design target for various transport protocols. Transport protocols however had additional design targets:

- Transport Agnostic

- The actual channel that a transport is implemented in should be irrelevant if the common component protocol was designed well enough. Transport protocols should be versioned to ensure compatibility.

- Connection Agnostic

- Transport protocols need to be agnostic of which side originates the connections. (Think the difference between a bind and reverse shell in MetaSploit)

- Transport Independent Encryption

- The operator can not rely on the transport layer to encrypt the data, encryption must be overlaid on top of the transport protocol. The encryption mechanism should be designed with enough robustness that the traffic of one transaction wouldn’t be enough to decrypt the rest of the traffic destined to it’s appropriate listening post.

- Chainable

- It may be necessary to chain implants together to some arbitrary length in order to interact with implants in a restricted environment. Implants must be able to chain together to provide a communication path to a listening post.

Future posts will delve into the common protocol developed for Shlyuz, the cryptographic model, challenges I encountered, architecture, and the tasking and communication model. Stay tuned for more updates.

seo tags: shlyuz - vault7 - implant - penetration_testing - red_team - assassin - CIA